Learning Resources

1. Introduction

LovingLearning.com.au, a Brisbane based training company has been engaged by the AFG Group to plan and develop an instructional design strategy and associated resources to ensure their 480 Australian based mortgage and finance brokers maintain compliance with the newly released National Consumer Credit Protection (NCCP) Act. Following an extensive gap analysis, design and development cycle, these resources have now passed internal quality assessment and are ready to progress to an initial pilot and rollout.

In continuing this work, LovingLearning.com.au will present a session plan for one of four eLearning modules entitled “NCCP for Brokers”, which itself will be critically appraised for its ability to fulfil the requirements of the client, including its alignment with the learning goal, objectives, strategies, and assessment. This will be followed by an exploration of possible alternatives to, along with the modules strengths and limitations which will then be weighed and balanced in summation.

The piece of work for AFG was a challenge for LovingLearning.com.au, as compliance based programs usually are. The penalties for non-compliance can be over one million dollars for corporations and $220,000 for individuals, and this has necessitated a far more behavioural and pragmatic approach than LovingLearning.com.au designers prefer. The success of this program however will be sufficient justification for the more prescriptive approach.

2. Overview

LovingLearning.com.au have created a program comprising of four eLearning modules of approximately one hourduration each. They are NCCP, Responsible Lending, Anti-Money Laundering and Privacy. For our purposes, we will be creating a session plan for and evaluating the NCCP module. This module consists of 44 slides, 13 interactions, 1 quiz, 1 video, 3 external links, and numerous voice over and audio soundtracks.

2.1. Theoretical and Philosophical Framework

Using the Smith and Ragan (2005) model of instructional design, LovingLearning.com.au assessed the subject matter and determined to primarily focus on behavioural change (Gredler, 2001). The legislative nature of the content, along with the severity of penalty should the learner disregard it led to a highly pragmatic and prescriptive approach.

Challenging the team to ensure the modules were still compelling and interactive, LovingLearning.com.au looked then to the theories of connectivism and experiential eLearning expounded by Siemens (2005) and Carver (2007) respectively in connecting to the more humanistic approach. The content had the potential to be very linear, dry and confusing however the team utilised many techniques in order to bring to life the more uninteresting section by enabling the learner to relate it to situations in their everyday work life.

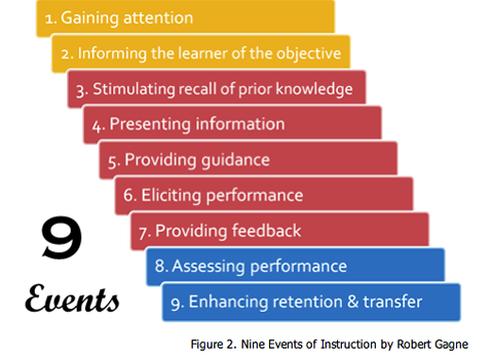

Having established this framework, the team turned to the work of Gagne, whose nine instructional events served as a suitable template through which to develop the sequence of the modules. These were later supplemented by significant levels of ‘pull’ content, as described by Hegel (2005), Felder and Brent (2005) and Richardson (2006). As opposed to ‘push’ theories, ‘pull’ requires that the learner find for themselves the content, questions and resources required to fulfil the learning problem. In the case of the NCCP module, these techniques have served to bring a level of interaction and challenge that would have been impossible before the advent of web 2.0 technologies.

2.2. Learning Goal and Objectives

Having established the theoretical and philosophical framework for the module, the learning goal was devised under both the guidance of the AFG subject matter expert and the aforementioned framework:

The learner will be able to identify all relevant requirements of the new NCCP legislation in the area of mortgage and finance broking, in addition to the responsibilities and ramifications of non-compliance. They will also be able to demonstrate the knowledge and skills required to maintain on-going compliance in both verbal and written communication.

This goal is consistent with the approach in that it requires both declarative and procedural knowledge (Gagne & Yekovich, 1993) of the content matter along with the utilisation of guided discovery, expository instruction (Mayer, 2002) and experiential eLearning (Carver et al, 2007).

The lesson objectives are spread across the four modules, however in this NCCP module, they appear as follows (see Appendix 1: NCCP for Brokers):

- Explain the fundamentals of the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009.

- Detail the obligations and penalties in relation to the Act

- Define the role of ASIC in regulating the role of credit providers

- List 6 ways to maintain compliance with the NCCP guidelines.

These objectives closely align to the learning goal, the theoretical and philosophical framework and the needs and interests of the learners themselves.

2.3. The Learners

The learners number more than 450 and range in age from 22 to 71. They are geographically dispersed across Australia from Tasmania to the Northern Territory in both capital cities and small townships. Their incomes vary from under $20,000 to over $750,000 per annum, and their level of experience in the industry ranges from three weeks to 42 years.

These factors, along with their approach to technology, attitude to education and indeed their basic literacy skills, conspire to make the role of LovingLearning.com.au in creating a quality learning experience a challenging one.

Whilst the learners may be diverse in some ways, they are uniform in their commitment to having already qualified for a Certificate IV in Financial Services. Furthermore, they are all currently undergoing a Diploma V upgrade to this course in alignment with a federal government mandate. They also share a common interest in and understanding of financial services, in addition to their collective agreement that a $220,000 fine from the governing body (ASIC) would be unpleasant indeed. These latter factors bring a unified pragmatism in simply “getting it done”

2.4. Types of Knowledge Targeted

The AFG brokers bring a wealth of knowledge, not only on the previous legislation but from all manner of other professions, educational study, cultural and social experiences. This knowledge needs to be respected and utilised as much as possible to ensure they actively engage in the content of the module. Cohen and Gelbrich described this phenomenon in 1999, as did Vygotsky who described the process of ‘scaffolding’ in 1986.

Both declarative and procedural knowledge will be targeted, naturally due to the prescriptive nature of the content. LovingLearning.com.au has no choice but to include a large quantity of legislation and text within the module. However, this alone will not provide the higher order knowledge such as conditional or strategic knowledge as described by Tayler in 1999. Having achieved an understanding of the new legislation, they brokers must be given the opportunity to explore when and how they might employ the new knowledge in the workplace.

It is for this reason that the team has created the broker simulations which feature in the assessment section of the module. These have been designed to prepare the brokers for their responsibilities under the Act going forward (Cohen and Gelbrich, 1999).

The guided discovery methodology, whilst less expedient that an expository approach, has been proven to result in better long term retention (Mayer, 2002). This is achieved by providing the brokers with real documents in the attachments section within the module.

2.5. Session Plan and Instructional Event

The session plan will run for one hour and be delivered entirely online. The module has been designed to be available through the existing AFG learning management system, SkillPort. The brokers will access Skillport, either from their home office or at one of AFG’s offices. They may do so at any time during the course of five days, their only obligation being to complete the assessment at the end of the module. This assessment will be automatically graded, timed and reported through to the human resources team at AFG.

There is a very clear advantage of presenting this type of information in an online platform through eLearning. Very simply, due to the high level of complexity and potential for confusion this content would be nightmarish to deliver in a traditional context. Given the diametrically opposed knowledge continuum on which the brokers sit, attempting to set a pace and level for the session would be near impossible.

In an online environment, the learner may take the appropriate amount of time they need in which to absorb the message. They can take a break should they need to, look up definitions at their own pace and work at a time of day that promotes their comfort and convenience. In a face to face context, people are reluctant to ask questions, revert to long engrained classroom style behaviours and often miss vital messages due to inattention, fatigue, linguistic difficulties or inappropriate pacing. Fletcher after carefully reviewing over forty independent studies found that Technology Based Training (TBT) yielded a time saving of 35-45% over traditional classroom instruction while obtaining equivalent or better gains in learning retention and transfer.

3. The Instructional Resource - NCCP for Brokers

The resource is part one of a four part eLearning series, entitled “NCCP for Brokers”. LovingLearning.com.au utilised rapid eLearning software to challenge and engage learners using video, sound, images, and interactive touch points. The project features the Engage, Presenter and Quizmaker software from Articulate.

It incorporates:

- images

- video

- flash

- animations

- case studies

- scenarios

- music / audio

In 2001, Nilan argued that students find their experiences in traditional classroom environments have almost nothing to do with their real lives. In this case, all the documentation, questions, scenarios and case studies have in fact been created to mirror the exact day to day operations of a mortgage or finance broker.

The design and development of this module was carefully scrutinised to ensure it catered to not only the more traditional learning styles, but also the emerging ones. For example, in 2005 Dede offered his "neomillennial learning styles", referring to Web 2.0, multi-user virtual environments, tablet computers and smart mobile phone. He proposed five new learning styles involving fluency in multiple media, communal learning, expression through non-linear associational webs, co-design of learning experiences and experiential learning. These are now the preferred or default learning styles of the younger brokers, so LovingLearning.com.au sought to incorporate these into existing eLearning technologies.

The audience of 450 brokers will be asked to complete the module during the course of five days. They may complete the course at home or at AFG offices, at any hour they wish. From the perspective of AFG, this project is very much about proving, should they need to, during an ASIC audit, that their teams have undergone the necessary training in order to comply with the legislation. Therefore, they simply require that the brokers log in to the Skillport system, complete the course and take the assessment during the time allocated.

There are no controls or processes that have not been considered, from deadlines, cut-offs, rotation of assessment questions, log in and password duplication, technological issues, browser updates and more. This is the advantage of outsourcing as LovingLearning.com.au have many years of experience in ensuring learning management systems record the right thing at the right time for the right people. Should the allocated team members and project owners fall sick or be unavailable during the five days, it will make no difference to the outcome of the project.

From a support perspective, there will be a coaching hotline set up during business hours for the brokers to utilise should they need to. In the event that they have a question concerning the content or a technical issue, they can simply contact AFG, who will have a LovingLearning.com.au representative in house for the duration in a support capacity.

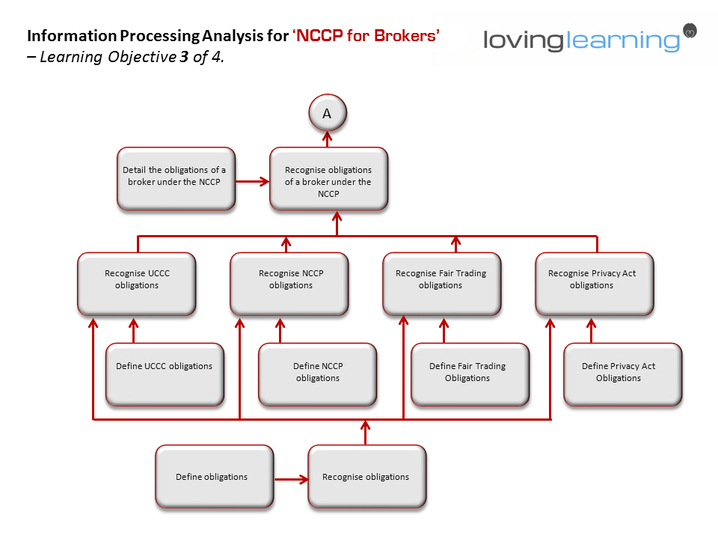

3.1. Information Processing Analysis

Task analysis was of vital importance to the team at LovingLearning.com.au. Smith and Ragan (2005) propose an instructional design process incorporating information processing analysis, which was used as a tool in this module to ensure brokers successfully navigate the learning objectives. A thorough Information Processing Analysis ensures that the instructional design of the eLearning module progresses in such a way as to support the mental steps necessary for brokers in interacting with the course content.

In Appendix 2, an analysis for learning objective 3 has been undertaken, ensuring the above mental steps throughout the learner’s progression in the module are clear. Following this stage was creation of the prerequisite analysis for each subsequent objective. Finally then, for each learning objective and assessment instrument was designed and developed and included in the module. The above steps were taken using the models of both Smith and Ragan (2005) and Gagne’s nine instructional events (1985).

3.2. Alternatives to eLearning

During the initial gap analysis and project kick-off meetings, the needs of both the organisation and its broker audience were discussed and documented in co-operation with the senior management team at AFG, in order to explore the optimum way in which to deliver the program. AFG were initially closed to the concept of eLearning, citing their need to ensure the brokers were actively engaged, achieved 100% attendance figures, were able to retain the key messages and understood the gravity of non-compliance. They had heard anecdotal evidence that eLearning struggles to achieve these and other requirements of programs based largely on a declarative and procedural knowledge platform.

For LovingLearning.com.au, who see tangible benefits being realised for clients on a daily basis, the choice was always going to be a technology based solution. Along with their gap analysis, they submitted a report to the AFG stakeholders, drawing on the substantial research conducted into technology based training interventions over the past twenty years. The report consisted of lengthy arguments, however to follow are five examples:

- studies have shown that eLearning can cut the travel and entertainment cost associated with training by at least 50% ( Hall 1997)

- Adams (1992) reported that eLearning produced a 60% faster learning curve as compared to traditional instruction

- Hemphill (1997) found that while eLearning saves time, it does not negatively impact effectiveness of learning

- Hall’s review in 1997 indicated that the reduction in time required in eLearning was 40-60% on average

- Adams (1992) found an average quality variance of 59% between presentations by classroom instructors.

For these reasons and more, the alternative face to face instruction was quickly dismissed, as it was proven to the AFG stakeholders that in this particular case, an eLearning intervention would be substantially cheaper, more effective and less time consuming. From their perspective, this allows them to not only save money on the wage bill of trainers, support staff and the brokers themselves, but also to completely suspend the need for flights, accommodation, meals and transport costs for all trainers and attendees. Once convinced of the quality results possible from well designer eLearning, along with the tracking and management statistics made possible by their LMS, they were in no doubt that eLearning was the best strategy for this project.

3.2. Module Strengths and Limitations

All instruction is an attempt to impose an artificial and created goal on a learner so that they may meet a set objective. In this way, no instructional event is perfect. However, in taking steps such as carefully analysing the learner, the context and the content matter it is possible to maximise the chances of a successful outcome.

The strengths of this modules are that it presents all necessary imagery, audio, video and documents in the one centralised location so as to enable the learner to complete the requirements in the once session, at the same time. The course is available to brokers from anywhere in Australia, on any technological platform they may have, from an iPhone to a personal computer. All content remains consistent from start to finish, and there is no change in the quality of the delivery.

The case studies and scenarios are taken from real life examples and as such will reflect the exact conditions brokers will be required to respond to. The content design is informed from a rigorous methodology based on tested models from Smith and Ragan and Gagne, and the AFG stakeholders are guaranteed to receive an accurate, timely and extensive report on which brokers have completed the module, how long they took to do it, how many times they attempted the assessment and what score they received upon completion.

As much as possible, the LovingLearning.com.au team have worked to ensure the limitations are accounted for, however given the medium of eLearning brings such substantial benefits, there are few but nonetheless notable balances. The program will be conducted over a 5 day period, during which the brokers must complete the modules. It is extremely difficult to ensure they do actually take the time to complete it. In a face to face interaction, they may indeed be asleep at the back of the room, but at least AFG are assured of their attendance.

Further, as brokers will be completing the module alone, there is no way of knowing if they are receiving assistance from a more experienced colleague in completing the assessment. This situation, in the experience of LovingLearning.com.au management, has been countered in the UK, where brokers routinely undergo phone testing as a means of ensuring they are not assisted. The content also, has been written and devised based on an assumed level of understanding and literacy. There is a possibility however small, that this could be misjudged.

Finally, the assessment component is limited to the scenarios and 23 questions which are rotated on a regular basis. Gauging the effectiveness of this will be completed in an initial pilot, but could be considered a limitation in that there is no guarantee that the broker will retain and utilise these knowledge and skills in the field.

4. Conclusion

LovingLearning.com.au has designed and delivered a pragmatic eLearning program using the Smith and Ragan instructional design model, which will provide learners with a challenging program in regulatory compliance, asking them to build both declarative and procedural knowledge of the subject matter, whilst providing opportunities to participate in guided discovery, conditional and strategic knowledge in ‘pulling’ web 2.0 technologies in order to complete the assessment and scenario based activities within the program.

The gravity of ramifications and penalties for non-compliance demanded a behavioural approach, ensuring the brokers did indeed know exactly what was required of them, however, when partnered with a connectivist strategy alleviated the typical pressure associated with such programs. The approach offers flexibility, interactivity and a solid grounding in achieving the desired real world learning goal and objectives.

Following a successful pilot and evaluation cycle, LovingLearning.com.au will deliver the program to all 450 brokers Australia wide. The LovingLearning.com.au team are satisfied that the requisite research, methodologies, cycles and liaison have ensured a quality program and that AFG stakeholders can now focus on their business expansion plans in 2012.

5. References

Adams, Gregory L. (1992, March). "Why Interactive?" Multimedia & Videodisc Monitor

Booth, R., Roy, S. & Clayton, B. (2004), Maximising Confidence in Assessment Decision-Making: Current Approaches and Future Strategies, NCVER, Adelaide.

Cantor, J. A. (1997). Experiential learning in higher education. Washington, DC: ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education.

Carver, R. (1996). Theory for Practice: A Framework for Thinking about Experiential Education, Journal of Experiential Education, May/June 1996 (Vol. 19, No. 1).

Carver, R., King, R., Hannum, W. H., & Fowler, B. (2007). Toward a model of experiential e-learning. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 3, 247-256.

Cohen, L. and Gelbrich, J. (1999). "Module One: History and Philosophy of Education". Retrieved September 4, 2011 from Ohio State University website: <http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/ed416/module1.html>.

Dede, C. (2005), "Planning for Neomillennial Learning Styles", EDUCAUSE Quarterly 7 (1), 7-12, date of access: 24 September 2011, http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/EQM0511.pdf

Dewey, J. (1938) Experience and Education, New York: Collier Books. (Collier edition first published 1963

Dick, W. & Cary, L. (1990), The Systematic Design of Instruction, Third Edition, Harper Collins

Driscoll, M. P. (1994). Psychology of learning for instruction. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Ertmer, P. and Newby, T. (1993). Behaviourism, cognitivism, constructivism: Comparing critical features from an instructional design perspective. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 6 (4), 50-72.

Felder, R. M. & Brent, R. (2005) Understanding Student Differences, Journal of Engineering Education 94(1) 57.

Fletcher, J.D. (1990, July). Effectiveness and Cost of Interactive Videodisc

Instruction in Defence Training and Education, Washington DC: Institute for

Defence Analyses.

Gagné, R. M., (1985) The Conditions of Learning and Theory of Instruction. New York: CBS College Publishing.

Gagné, E. D., Yekovich, C. W., & Yekovich, F. R. (1993). The cognitive psychology of school learning. (2nd ed.). New York: HarperCollins.

Gonzalez, C. (2004). The role of blended learning in the world of technology. Retrieved September 5, 2011 from http://www.unt.edu/benchmarks/archives/2004/september04/eis.htm

Gronlund, N. E. & Waugh, C. K. (2009). Assessment of student achievement (9th ed.). New Jersey: Merrill-Pearson.

Gulikers, J., Bastiaens, Th. & Kirschner, P. (2004) A five-dimensional framework for authentic assessment, Educational Technology Research and Development, 52(3), 67-85.

Hagel, J.(2005) From Push to Pull, date of access: 24 September 2011, http://www.johnhagel.com/view20051015.shtml

Hall, B. (1995). "Multimedia Training's Return on Investment.,Workforce Training News, Q3, 95

Hemphill, H., H. (1997) The Impact of Training on Job Performance, NETg white paper retrieved on 25 September, 2011 http://www.llmagazine.com/e_learn/resources/pdfs/ROI_training.pdf

Ireland, T. (2007). Situating connectivism. Retrieved September 5, 2011, from http://sites.wiki.ubc.ca/etec510/Situating_Connectivism

Krause, K., Bochner, S., Duchesne, S. (2003). Educational Psychology for learning and teaching. Victoria: Thomson.

Mayer, Richard, E. The Promise of Educational Psychology Volume II: Teaching for Meaningful Learning. Pearson Education, Inc., New Jersey, 2002.

Nilan, P. (2001), "From 'Sesame Street' to the 'Soapies': Classroom Politics and popular culture" in Sociology of Education: Possibilities and Practices, ed Jennifer Allen (Katoomba: Social Science Press)

Reigeluth, C. (1983). Instructional design theories and models; an overview of their current status. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Richardson, W. (2006) Blogs, Wikis Podcasts, and Other Powerful Web Tools for Class-rooms (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press).

Siemens, G. (2005, January). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Technology & Distance Learning

Shambaugh, Neal R. & Magliaro, Susan G. (1997). Mastering the possibilities, A process approach to instructional design, Needham Heights, Allyn and Bacon.

Smith, Patricia L. & Ragan, Tillman J. (2005). Instructional Design, 3rd, Holboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons

Stollings, L. (2007). Robert Gagné’s nine learning events: Instructional design for dummies Retrieved on 10 September 2011 from: http://sites.wiki.ubc.ca/etec510/Robert_Gagné%27s_Nine_Learning_Events:_Instructional_Design_for_Dummies

Taylor, S. (1999). Better learning through better thinking: Developing students’ metacognitive abilities. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 30(1)

Tulving, E., & Schacter, D.L. (1990). Priming and human memory systems. Bum. Science, 247, 301 – 306.

Vaill, P. B., (1996). Learning as a way of being. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc

Vygotsky, L.S. (1986) Thought and Language. Boston: MIT Press

9. Legislation

The National Consumer Credit Protection (NCCP) Act 2010 – Australian Government

10. Appendices

1. NCCP for Brokers - eLearning Module example

2. Information Processing Example - Learning Objective 3

3. Gagné’s 9 Instructional Events

4. Siemens Theory of Connectivism

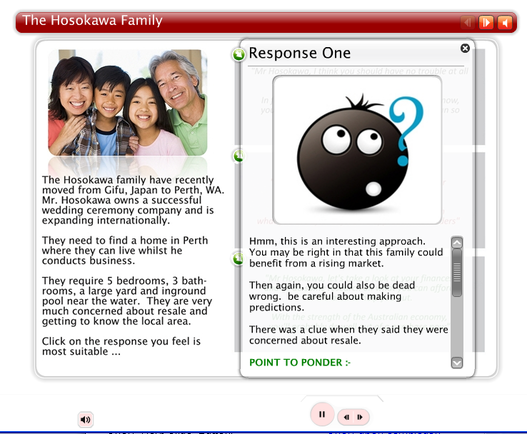

10.1. Appendix 1 – NCCP for Brokers - eLearning Module example

10.2. Appendix 2 - Information Processing Example - Learning Objective 3

10.3. Appendix 3 - Gagné’s 9 Instructional Events

10.4. Appendix 4 - Siemen’s

Theory of Connectivism